Go Back

News

Alumni Stories

Alumna Weiwei's Journey: Redefining Design in the Age of AI

Alumni Stories

07 Aug, 2025

11 : 41

On a warm early summer afternoon in Shanghai, Weiwei joined the video call, dressed in a black T-shirt and looking relaxed, as though she had just finished a long day at work.

We conducted the interview remotely. She spoke with ease and humour, often peppering the conversation with playful remarks and rhetorical questions — "That professor just calmly exploded," "I had no direction at the time," "That was really cool." What might have been a serious interview quickly felt like a chat between friends.

Weiwei never tried to shape her creative journey into a neat, linear narrative. Instead, she preferred to unpack the process, loop back, and ask herself again and again: "Why did I choose that at the time?"

When talking about Lentil, the image rendering tool she's currently developing, she focused less on funding or user growth, and more on the question: "How can expression be made more intuitive, more human?"

After graduating from YCIS Shanghai Pudong in 2014, Weiwei went on to study at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. She initially enrolled in industrial design, but after a year of sanding models every day, found it mind-numbingly dull and swiftly switched to interaction design.

During her time at university, she interned at consulting firms, worked as a lab assistant at the world-renowned incubator Dynamicland, and began using design thinking to tackle challenges beyond the realm of physical products—gradually moving into more complex design contexts.

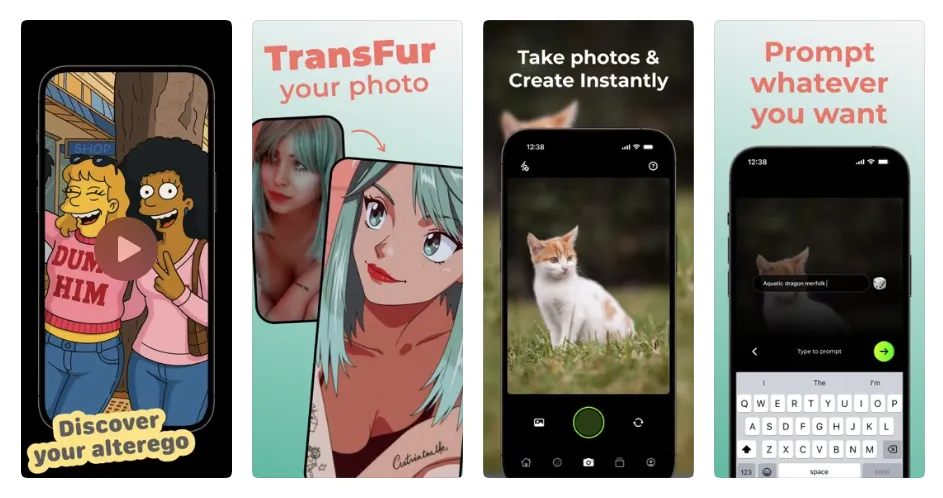

In 2020, she launched an AI-powered video tool called Tonic, which made an instant impression. Within a month, it had surpassed a million views, with an average user share rate of over 83%. Now, she's devoting herself to the development of Lentil, an image rendering tool that is already generating anticipation ahead of its release.

She's very much a night owl when it comes to creativity—brainstorming, editing decks, reading papers deep into the night, then sleeping during the day to recharge. Outside of work, she finds joy in rock climbing: a test of physical limits and a highly effective way to unwind.

What follows is her story, in her own words.

🎨

From Portrait Fails to a Designer's Intuition

I remember when I was little, people would ask me, "What do you want to do when you grow up?" At the time, my answer was always: I want to be a designer. My head was constantly filled with questions — why is this table so uncomfortable? How could it be improved? Why is this can so unhygienic? How could it be redesigned? That kind of thinking came naturally to me, and made me feel like design was a way to fix small, annoying problems in life.

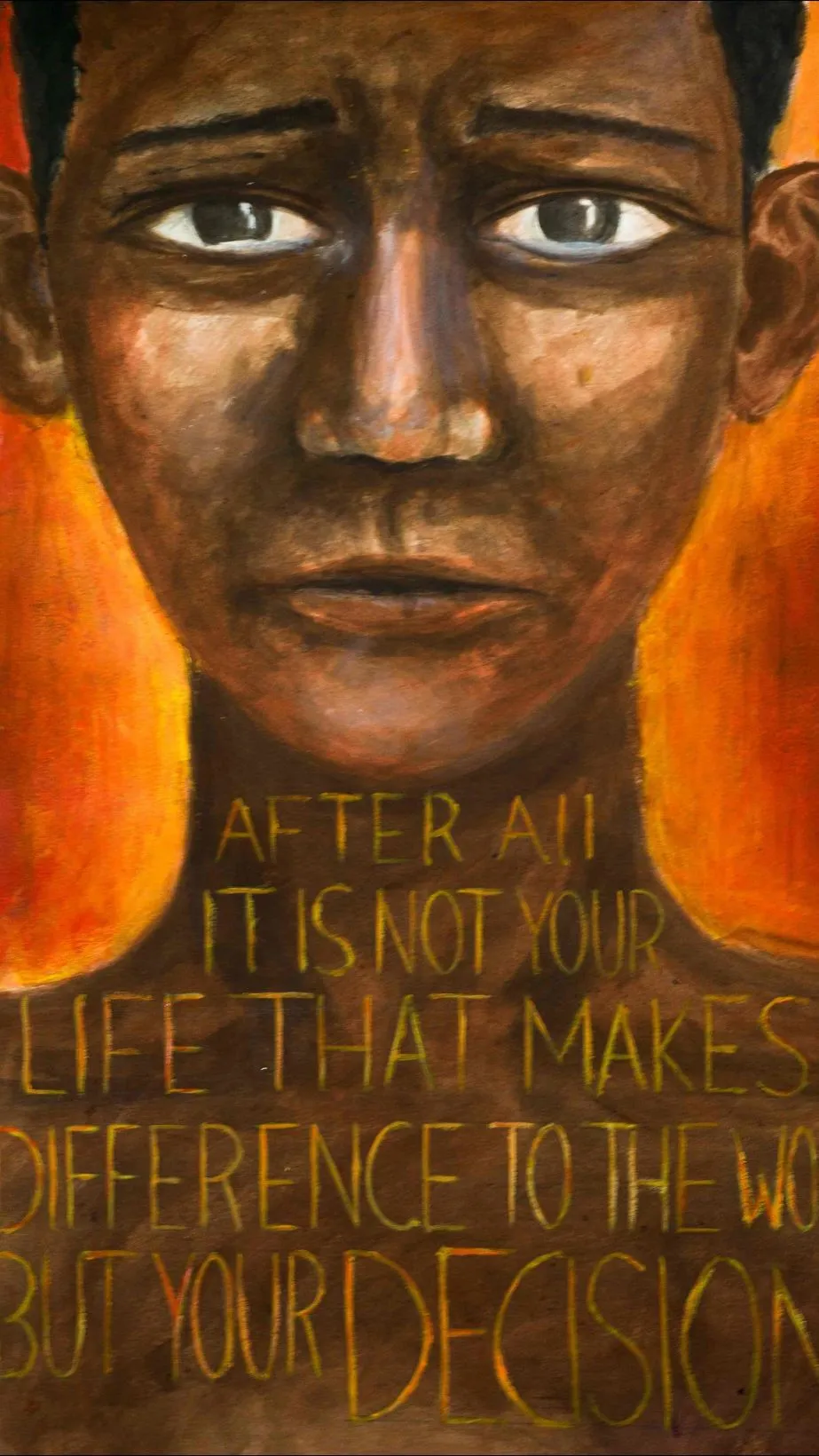

Before joining YCIS, I only really knew how to draw landscapes. Portraits were a disaster — no proportions, no sense of structure. Once, in art class, I completely botched a face. The teacher looked at it and said, "Don't leave just yet. Let's finish it together." She taught me how to shade, how to emphasise features.

That was the first time I managed to draw something that resembled a human face. Later I realised that for a lot of things, as long as someone is willing to stand by you through that early stage of uncertainty, things eventually start to click.

|

|

|

|

|

|

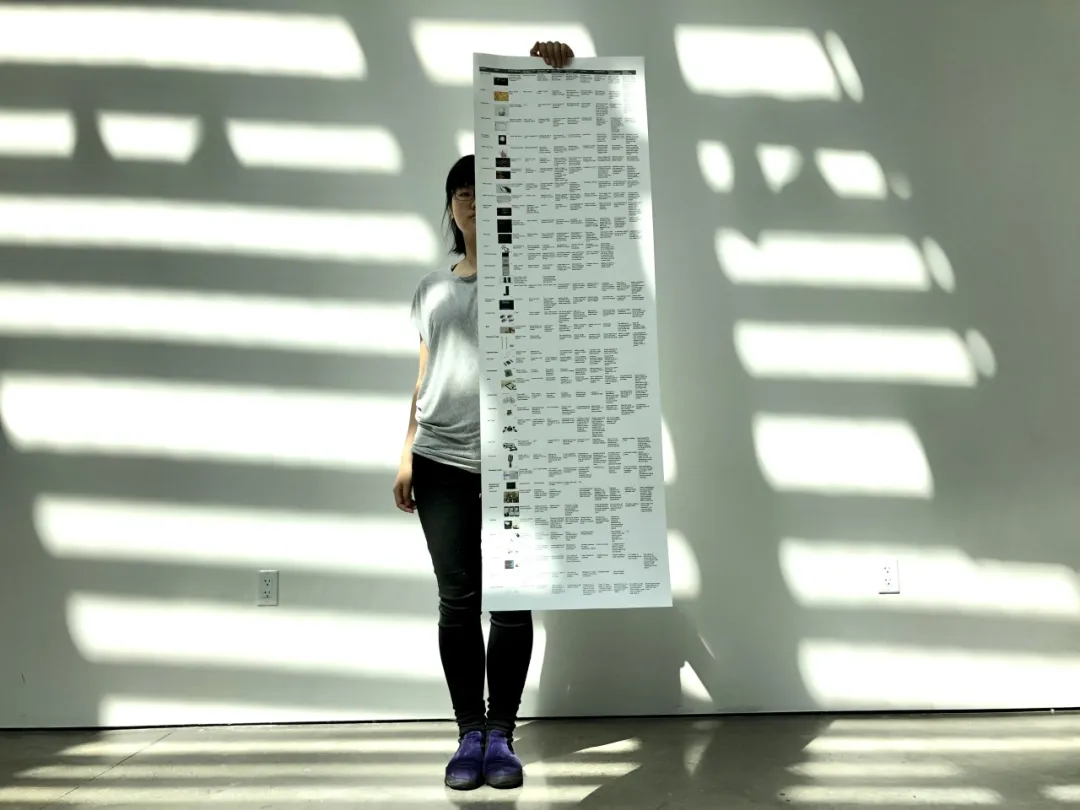

▲ Part of Weiwei's IB Artwork

YCIS gave me a lot of room to try, to propose ideas, and to make them happen. We pushed for a Design and Technology course under the IB curriculum, and I initiated the Art Student Council.

▲ Weiwei sharing her experience at YCIS Shanghai after graduation

We did everything from decorating events to designing covers for school publications. I worked with others to turn hand-drawn artwork into bookmarks and print them in school magazines, designed a student diary that was actually used, helped create our Yearbook, designed posters for performances, and even worked on magazine covers for outside organisations.

At the time, I was especially drawn to the idea of "beauty you can use." I wouldn't have said I was particularly talented — but I was definitely busy, engaged, and above all, fulfilled.

Scroll down to view the YCIS Shanghai diary designed by Weiwei

|

|

|

▲ Cover designed by Weiwei for Shanghai Family

💻

My Time at Dynamicland

When I first enrolled at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, my major was industrial design. But after a year of sanding down models every day, I found it far too monotonous and quickly applied to switch to interaction design.

By chance, I came across Dynamicland, a well-known research organisation founded by interaction designer Bret Victor. As soon as I saw their work and the projects they were developing, I felt a surge of excitement—this was exactly the kind of thing I'd always wanted to do, but never knew how to approach.

I ended up reading almost everything I could find about Dynamicland: articles written by the team, blog posts, public-facing project documents.

Whenever I came across acknowledgements at the end of an article, I would look up the names mentioned and follow them on Twitter. I simply wanted to get as close to that world as I could—even if there wasn't a door yet, I wanted to stand just outside the frame.

Later, through my teacher at Humanites class, I was given the chance to visit their lab, which eventually led to an internship.

As an intern, I did a bit of everything—from taking down experimental notes and conducting user testing to writing up basic documentation. The work was fiddly, hands-on, and lacking in clear standards, yet deeply absorbing. It felt as though I was learning through doing, almost like taking part in a quiet, ongoing rehearsal of ideas.

▲ Weiwei(far right) with her colleagues at Dynamicland

I remain incredibly grateful for that experience. It was the first time I realised that "design" isn't just about producing something beautiful—it can also be a way of opening up the world, organising knowledge, and even framing the right questions. After that, my perspective on things shifted quite profoundly.

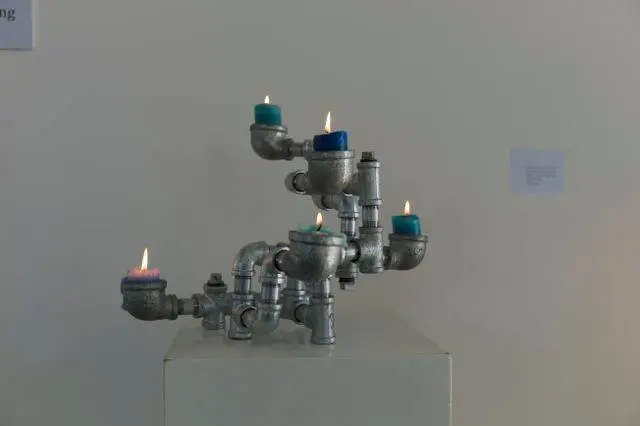

That internship also inspired my thesis project, Defining the Dimensions of the "Space" of Computing. I explored the essence of what computing really is, and how design might help us better understand and organise information in the digital world. The paper was later published in the MIT Press Journal, which gave me a tremendous boost of confidence.

▲ Weiwei's undergraduate thesis

🌍

Crossing Fields Isn't About Jumping—It's About Bringing Things With You

A lot of people describe me as "interdisciplinary"—design, tech, product, content, startups… But I never felt like I was switching fields. It's more that I just kept walking forward, and along the way, I brought with me things I'd learned before.

For example, when I was building Tonic, I thought back to my earlier research on the music industry—how musicians create a style with the bare minimum of material. Later, when I started building Lentil, that thinking stayed with me. We didn't start by designing a tool. We started by asking: What kind of tone do people want when they express something? How can we help them say something clearly, in their own way?

▲ Lentil on the Apple App Store

I love what the American singer John Mayer once said: "You can't fit the entire ocean into a glass of water, but you can describe a glass of water so vividly that it feels like the whole world." The secret behind anything truly compelling is hidden in that one glass of water—not in chasing big numbers, but in paying attention to small, human moments of expression.

🧗

My Anchor in the Chaos: Climbing

Although work and thinking take up most of my time, I've found a very specific way to reset and recharge: climbing. When I'm on a wall, all my focus narrows down to the next handhold or foothold—how to balance, how to move efficiently. It's like my body is having a direct conversation with the surface in front of me, and in that moment, the daily noise just falls away.

Climbing isn't just physical for me—it's a way to declutter my mind. Every time I finish a route, that feeling of achievement and physical clarity gives me a fresh burst of energy. It helps me return to work more grounded, with sharper thinking and a clearer head.

▲ Weiwei while rock climbing

💬

From her early instinctive curiosity about "useable beauty," to her time at Dynamicland where she came to see design as a way of asking questions, and now to her pursuit of intuitive modes of expression, Weiwei's path has never been linear. Instead, it spirals upward—each stage folding into the next, shaping an ongoing journey of integration and exploration.

To her, design is not just a tool for making products, but a way of understanding the world and solving problems. Her story quietly reminds us that the most exciting forms of innovation and growth often happen when we break boundaries, embrace complexity, and keep returning to the question: "Why did I choose that, back then?"

Lentil, the project she's working on now, may well be the latest expression of this way of thinking—using technology to make communication, one of the most instinctive and deeply human acts, more honest and more pure.